Big Data Helps Space Optimization But Barriers Remain

Open any business publication and you’ll probably find an article about Big Data.

GE has sensors on jet engines and uses that data to inform maintenance issues. Facebook, Amazon and Expedia collect reams of data to better attract and serve customers. Higher education is also leveraging Big Data. IBM recently posted an article on how universities are using data analytics for recruitment and retention.

We also see Big Data as a tool to improve space optimization, a big issue on many campuses. Not only do many institutions face financial constraints with being able to add space, but space optimization is also increasingly tied to sustainability.

Many institutions have room for improvement. A typical classroom is occupied less than 60 percent of the time, says Sightlines, which helps institutions better manage facilities. An analysis of teaching lab space in 2014 throughout the North Dakota University System found labs being used an average of 13 hours a week.

Where’s the Math?

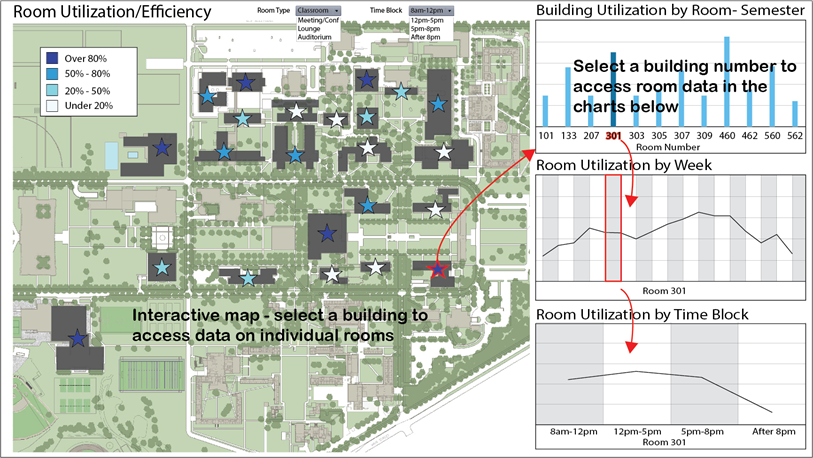

We work daily with clients to get the most out of every square foot, whether that be in new construction or existing space. Powerful software that wasn’t available even a decade ago now enables designers to more easily overlay scheduling on top of building and room data, down to how many seats are in the room and whether the layout is flexible. What’s more, clients are now asking questions they haven’t asked before. They want data to back up decisions as to why they need new conference rooms, for instance, and why those types of rooms meet student needs better than others. In short, they want to see the math to back up their space decisions.

Yet good data can be hard to come by. Outdated scheduling systems, for instance, may not link data between departments to give a full campus view. Also, institutions may have a hard time figuring out how space is being used because of a lack of unified data and information that’s stored in multiple databases. To get better data, more institutions are experimenting with automated data collection, tracking energy use to find nodes of activity or using light sensors to detect room use. Institutions also continue to survey students on how and where they spend their time.

These types of efforts will only increase in frequency and creativity. That's because having good data is key to winning over faculty and staff when space decisions are made and space allotments change. Academics are, after all, accustomed to working with data and know its value.

Hindering Space Management

Even with good data, however, entrenched ways of doing things may hinder an institution’s ability to make changes, and to do so amicably.

Huron Consulting Group, in an assessment of space utilization at the University of Colorado — Boulder, identified key themes that hinder effective space management at all kinds of schools. Those were:

- The lack of price, which, Huron concluded, “leads to a perception that space is a free good which tends to lead to overconsumption.”

- The lack of a shared way to allocate space, which leads departments or others to retain use of space they no longer need just in case.

- The lack of a mechanism to determine “highest and best use” of space on a university level.

- A culture of departmental ownership of space rather than one in which departments put “stewardship” of university space first and foremost.

Huron also noted lack of good data as being a problem and the “informality through which many space decisions are made.” That means that, oftentimes, space decisions made years ago remain in place even though they’ve far outlived their useful lives.

Big Data will help schools tear down all of these walls to increase their space optimization. It’ll also help inform when, where and if new walls need to be built to meet enrollment, teaching and learning needs. After all, the most sustainable building of all is the one that’s never built.

This post was written with contributions from Jimmy Stevens, LEED AP