Incentives Helping to Drive Green Power on College Campuses

Higher education has been steadily increasing its use of renewable energy and an extension in federal tax credits, we think, will usher in even more.

In December, Congress extended the 30 percent federal solar investment tax credit, which was to drop to 10 percent this year, through 2019 at the full 30 percent and then gradually reduce it to 10 percent in 2022. The wind production tax credit, which had expired in 2014, was retroactively applied to 2015 and extended through 2016, after which it will decline until it expires in 2020.

Most universities and colleges can’t tap these credits because they don’t pay taxes. But dozens of schools are benefiting from the incentives through the use of so-called power purchase agreements.

With PPAs, a private developer builds, runs and maintains a solar installation, for instance, on or near the school, takes the 30 percent tax credit and the school gets energy at a lower cost. One big plus is that the school doesn’t have to foot any upfront costs. Instead, it pays a monthly bill just as if it was paying a regular electrical bill.

So far, schools in at least 16 states, including California, Arizona, Virginia, Ohio, Minnesota and Maine, have signed PPAs to produce 100 megawatts of solar power, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory says.

All told, growth in solar production via PPAs for higher education grew at an annual rate of 23 percent between 2010 and 2015, NREL says, citing data from AASHE, the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education.

Of late, more schools have also been adopting PPAs that involve use of off-site locations. That’s because many schools simply don’t have the roof space to accommodate enough solar panels to produce all of their energy, or space to set up massive wind towers.

In 2014, the Washington D.C.-based George Washington University, American University and the George Washington University Hospital announced a deal with developer, CustomerFirst Renewables, to build the largest solar photovoltaic power project east of the Mississippi River. The project is located in North Carolina.

Last year, Stanford University partnered with SunPower to build an off-site solar farm in southern California to deliver half of the university’s electricity. The “renewables by wire” project allows for a larger solar installation than would be possible on the land-constrained Stanford campus.

Barriers to adoption

Despite the progress, barriers exist for higher education and renewables.

Many PPA contracts run for 15-20 years. Many schools aren’t accustomed to signing on for such long-range projects. Getting one done involves representatives from many different school departments, from site planning to procurement and legal.

What’s more, the installations can be massive and complex and no one should put anything on a roof, or put a wind tower in a field, without understanding all of the implications.

When Stanford decided last year to install rooftop solar, it audited and analyzed more than 60 campus sites for suitability, based on aesthetic, historical impact to campus, along with orientation to the sun, roof size, slope and construction.

Policy has also been a barrier. In a handful of states, including Florida, PPAs are not allowed, mainly because of state regulations having to do with local utilities.

Cost can also be a barrier for schools. Solar PPA prices have fallen 70 percent since 2009, indicates a report by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab). Meanwhile, the cost of wind power has dropped at least 60 percent in the last five to seven years, NPR recently reported. Still, some schools can get better energy deals from local utilities.

Finding the right incentive

Finding all of the available incentives, and working with them, can also be challenge. The federal tax incentive for wind production, for instance, had expired before Congress in December made it retroactive to 2015.

There do exist good tools to find other incentives, too, especially state ones which vary, unlike the federal ones.

The most well known database is perhaps the DSIRE database. Found here, it is funded by the Department of Energy and maintained by the NC Clean Energy Technology Center.

Another tool to get specific state information on renewables and incentives can be found here at the State Policy Opportunity Tracker provided by the Center for the New Economy in Colorado and the Nature Conservancy.

More resources have also sprung up to help universities and colleges navigate the pursuit of renewables. NREL, for instance, offers no-cost technical assistance, including site analysis, to universities seeking to go solar.

Private companies, too, have moved into the field. The Boston-based Altenex company, for instance, helps match companies and universities with renewable energy developers.

Even if the federal tax credits expire this time as planned, we still expect more development of renewable energy in higher education.

For one thing, the cost continues to drop, which makes the incentives less important.

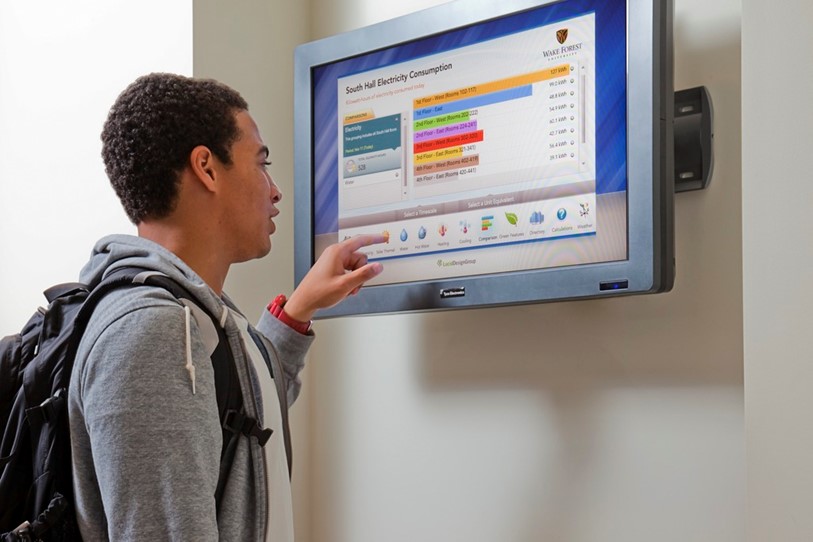

Second, people love green power. The investor interest in the electrical car maker, Tesla, shows how much this is true as the stock is routinely dubbed “overvalued.” College students are likely to remain on the frontline of this revolution. To keep attracting those students, as we noted in an earlier post, schools will have to continue to build and tout their investments in green energy.

The University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, for instance, recently announced that it had become the first university in that state to have 100 percent of its electricity come from renewable sources. About 30 colleges and universities in the country are already at this point, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Green Power Partnership. We expect to see more schools, year after year, meet that same goal.

This post was written with contributions from Jimmy Stevens, LEED AP