Space: More Than Square Footage Per Student

Improving space utilization is increasingly a top priority at higher education institutions. Colleges and universities looking to reduce carbon footprints want to avoid new construction yet still provide top educational experiences. Financial constraints on state governments means limited or reduced funding for public institutions, so use of existing space becomes all the more important. Many studies have documented classroom use. We think there’s more to space utilization than how often a room is occupied. What happens inside an occupied room is just as important.

In a previous post, we talked about the growth of Scale-Up Classrooms. Scale-Up, or Student-Centered Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies, is in use at more than 250 higher education schools. The classrooms look like restaurants, with round tables for student seating. There’s no professor behind a podium at the front of the room, lecturing, while students sit side by side in chairs—a classroom design in place since medieval times. Indeed, there is no “front” of the classroom at all. In a Scale-Up, or active learning classroom, students work in small groups as teachers roam among them.

At face value, Scale-Up classrooms may not hold as many students as lecture halls, but as I found there is more to space utilization than just counting seats. This can be an issue for some schools. To explore the issue of space and Scale-Up, I interviewed Robert Beichner, the physics professor who pioneered the Scale-Up classroom in the mid 1990s at NC State University. He brings new considerations to the space optimization equation. Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

Q: How is classroom space wasted in traditional lecture halls?

A: A lot of space in a lecture hall is reserved for the teacher. If people sit in the front row of student seating and count ceiling tiles, or something, they’ll realize that they’re sitting a quarter to a third of the way back in the room. Maybe there’s a whiteboard in the front of the room, space in front of that, a teacher table, and space in front of that. In Scale-Up, there is no reserved space like that. It is almost all student space.

Q: What about the cost of Scale-Up per square foot vs. a traditional classroom?

A: It’s not that much more expensive. It does depend on the technology you put in there. The furniture, the chairs, are about the same. Large screens and microphones add costs. In smaller spaces, you can get by with a lot less technology, less audio, fewer shared screens. You can just look across the room instead. But if you’ve got 100 students, you’d need microphones and shared screens.

Beichner recommends nine students seated at seven-foot round tables in groups of three with each group sharing a computer.

Q: Have you ever substituted Scale-Up for a regular classroom in the same space and accommodated the same number of students?

A: Yes, almost one-to-one. (https://www.ncsu.edu/PER/Articles/Chapter.pdf, page 24.)

In Phase 2 of the Scale-Up classroom development a 55-seat traditional classroom was renovated into a 54-seat Scale-Up classroom, providing a nearly one-to-one conversion.

Q: What space issues can’t you measure in Scale-Up?

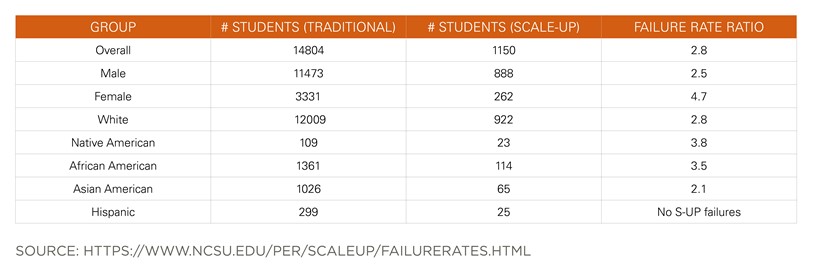

A: You may have (more) seats in a lecture hall … but if 40 percent of them are empty and students aren’t showing up, that’s wasted space. It’ll all depend on whether attendance is required, whether there are tests and on how good the lectures are. In my Scale-Up classrooms, attendance over five years averaged 93 percent without attendance required. Typically, failure rates also drop from 30 percent to 10 percent with Scale-Up. That’s a substantial number of students who won’t be taking a class two or three times, so what happens is, without adding a physical seat, you increase the capacity of the space. Plus, it’s really nice not to have to fail people.

Q: Does Scale-Up also work as lab space?

A: Scale-Up can replace both a lecture and a lab room and combine them into one. If that happens, you’ve gone from needing two rooms down to one. Equipment can be an issue. If you need to pipe gas, for instance, have fume hoods or sinks. In some Scale-Up rooms, that equipment will just be put off to the side (around the perimeter of the room) because you’re not using it everyday, things like expensive microscopes or even sinks on platforms.

During a previous site visit to meet with Professor Beichner in a Generation 4 Scale-Up classroom we noticed a mobile cabinet with sink, which he said is another option for lab demonstrations.

Q: With technology and computers, is there potential to displace some of this hands on?

A: That may be possible but I‘m not sure it’s a good idea. Simulation, no matter how good, is not the same as doing by hand. Even in a Scale-Up classroom, I wouldn’t suggest that simulations replace real world activities. However, it can supplement them.

Q: In the campus of the future, do you see the number of Scale-Up classrooms rising and taking up more of a school’s space?

A: Probably, especially as more online education becomes available. If it is cheaper and more convenient to take an online class, it’ll be hard to justify more lecture. There’s been a lot of study to show that online is at least as good as lecture. Lecture can’t compete with Scale-Up in terms of learning, to say nothing of the soft skills, like communication and teamsmanship, that students get with Scale-Up. In the future, you’ll go from lectures at the low end to distance education. The next level up will be Scale-Up. Schools that really push the personal connections among students will be more able and willing to pay for Scale-Up.

Q: Are students fearful of this continual engagement in this kind of space?

A: We do explain what we’re doing and why. We are violating their expectations of what should happen in the classroom. I’m honest with them. I tell them, “if you don’t have the time or energy to devote to this, then you need to change classes because you’re going to have to work hard but it is worthwhile.” Then, they realize that this is a serious undertaking.

Q: If you could start from scratch, how would a new Scale-Up be different?

A: It would be square so that every student in the room could see every other student.

Currently, Beichner believes the ideal classroom geometry is non-directional so tables have the greatest equality possible from the professor podium (center) and perimeter wall (flat panel, writing surface), as well as sight lines from any point to any point.

Q: What are the biggest obstacles to adopting Scale-Up?

A: It takes a different philosophy. People who’ve been teaching a certain way for a long time don’t want to change. People don’t want to admit that what they’ve been doing for a long time isn’t very effective. It also requires a lot of competence and confidence on the part of instructors because students really test them with hard questions. That’s quite a bit different than delivering a planned lecture with little time for student questions. Finding money for the space can be difficult, too, but it can also help. (To pull it off,) you need a team of people, faculty and administrators, getting together to talk about teaching and learning. That’s a good idea. If they spend money and effort on a space like this, they’re less likely to return to traditional instruction.

Q: Have you found any unexpected results from Scale-Up?

A: After activities, I ask students to hand their notebook to the student on the right and spend a couple minutes writing down what they think the take away was from the activity, and then hand the notebook back. First, I found the students wanted more time to write about science, which is pretty unusual. That indicated that they were taking it seriously. The whole idea is to get students evaluating, presenting to the class and telling the class that what (other students) wrote is worthwhile. This kind of public validation really makes a difference in how the class feels.

This post was written with contributions from Jamey Glueck, AIA, LEED AP BD+C